My motherhood experiences have been vast and varied. I know what it is like to wait until my next paycheck before my next purchase, to live at home with my child in my mother’s basement and take my son’s biological father to court to fight for financial justice; I also know what it is like to live overseas and to travel with my son to our 50th country when he is 15 years of age.

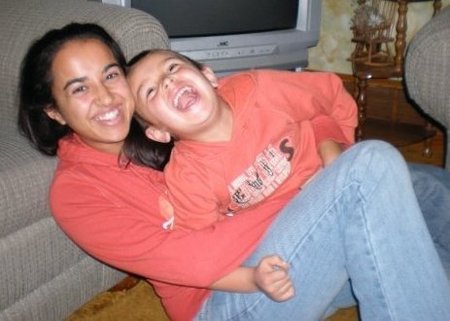

My single-lone motherhood has become an integral part of my identity. I seek to share stories that disrupt most mainstream narratives of single teen motherhood, which often frame female-led households around an absence as opposed to the fully complete, loving, and healthy families that exist, a more accurate picture of the life my son and I have built together.

My single-lone motherhood has become an integral part of my identity. I seek to share stories that disrupt most mainstream narratives of single teen motherhood, which often frame female-led households around an absence as opposed to the fully complete, loving, and healthy families that exist, a more accurate picture of the life my son and I have built together.

Excerpts from Research Papers

Excerpt from Single-Lone Mothers: The Movement

This excerpt looks at issues with research that suggest that single motherhood in and of itself is problematic.

This excerpt looks at issues with research that suggest that single motherhood in and of itself is problematic.

“‘Single mother.’ Say it out loud in a grocery store, at school, in the park, on the news, or in a social service agency and all of the destructive and pathologizing images of a neglectful mother come to mind” (Ajandi 411). Structural and institutional disadvantage plays an important role in the creation of this, and more often than not does not reflect the reality of many mother-led households. While there are indeed single fathers who face their own challenges, "[t]he gendered reality of parenting alone [is] that it is still predominately women and mothers (‘women's work’) who are engaged in the bulk of the labour of childrearing" (Motapanyane 2).

At the most basic level, it is important to ask – who are single mothers? Bruno states that single mothers are “a group of women who are notoriously difficult to identify, let alone define” (385). The author understands single mothers as women who parent outside of the nuclear family structure, “but in no way assumes singleness indicates a lack of personal or parental companionship” (Bruno 385). In this way, it is noted that a single mother may or may not have other parental figures helping to raise their child. Single motherhood is also not always a static group - it is sometimes a temporary state, not a permanent one (Bruno 389). Bruno notes that “...single motherhood looks different for every woman…the diversity of terms for single motherhood (“single mother,” “lone mother,” “solo mother,” “female headed household,” etc.) reflects a ‘real diversity of meanings and experiences’”…[which also reflects] shifting ideologies over the last century” (388).

Families with single mothers at the head of the household are continuously seen as a second-hand, less-than-ideal option in Canadian society – and many others around the world. One reason for this is the perceived detriment it is seen to inflict: it is believed that single mother households are not good for children’s well being. This includes viewpoints that children raised by single moms are less likely to complete high school, and more likely to be neglected and/or raised in impoverished conditions. Hunter notes, “[h]ealth and social researchers overwhelmingly report poorer well-being for women and children in lone-mother or single-parent families, as compared with two-parent households…[r]esearch into life in mother-led or lone-mother households is dominated by negative accounts of deficit or survival” (222-228). Yet Hunter goes on to state,

research academies have been found to reflect a particular conservative, individualistic, and patriarchal valuing of well-being, women and children, as well as a preference for certain gender functions and the promotion of normative (nuclear) family forms…[s]ome researchers demonstrate a visible preference for the supposed benefits of living in two-parent families…beside such an agenda, lone-mother families continue to be viewed as deviant. (235)

In the face of such research, then, single mothers must overcome negative stereotypes and life narratives forced on them while simultaneously raising a child solo. Hunter asserts that it is important to assess the societal values of and around researchers and to consider how this may have an effect. Of course, this is not to say that single mothers do not face challenges and societal disadvantages – for as Hunter notes that among people who experience chronic stress, economic disadvantage, and discrimination, single mothers are overrepresented.

Yet as research findings have been lacking in showing the strengths and advantages of single mother families, an effort is needed “…to extend forms of fieldwork to include informal, narrative, and online sources as well as to commit to researcher reflexivity across all methodologies which acknowledge rather than ignore the embedded values of the researcher” (Hunter 236). As Bruno notes, many who now write about single motherhood object to framing single motherhood as an absence (386). Moving forward, researchers must acknowledge the effect that their work has on the lives and well-being of women and wider society: “[r]esearch that reinforces and reproduces a deficient evaluation of single-parent families requires re-examination” (Hunter 235). Hunter “...urges researchers to listen more carefully to the voices of women and respect their accounts of their own lives” (236).

At the most basic level, it is important to ask – who are single mothers? Bruno states that single mothers are “a group of women who are notoriously difficult to identify, let alone define” (385). The author understands single mothers as women who parent outside of the nuclear family structure, “but in no way assumes singleness indicates a lack of personal or parental companionship” (Bruno 385). In this way, it is noted that a single mother may or may not have other parental figures helping to raise their child. Single motherhood is also not always a static group - it is sometimes a temporary state, not a permanent one (Bruno 389). Bruno notes that “...single motherhood looks different for every woman…the diversity of terms for single motherhood (“single mother,” “lone mother,” “solo mother,” “female headed household,” etc.) reflects a ‘real diversity of meanings and experiences’”…[which also reflects] shifting ideologies over the last century” (388).

Families with single mothers at the head of the household are continuously seen as a second-hand, less-than-ideal option in Canadian society – and many others around the world. One reason for this is the perceived detriment it is seen to inflict: it is believed that single mother households are not good for children’s well being. This includes viewpoints that children raised by single moms are less likely to complete high school, and more likely to be neglected and/or raised in impoverished conditions. Hunter notes, “[h]ealth and social researchers overwhelmingly report poorer well-being for women and children in lone-mother or single-parent families, as compared with two-parent households…[r]esearch into life in mother-led or lone-mother households is dominated by negative accounts of deficit or survival” (222-228). Yet Hunter goes on to state,

research academies have been found to reflect a particular conservative, individualistic, and patriarchal valuing of well-being, women and children, as well as a preference for certain gender functions and the promotion of normative (nuclear) family forms…[s]ome researchers demonstrate a visible preference for the supposed benefits of living in two-parent families…beside such an agenda, lone-mother families continue to be viewed as deviant. (235)

In the face of such research, then, single mothers must overcome negative stereotypes and life narratives forced on them while simultaneously raising a child solo. Hunter asserts that it is important to assess the societal values of and around researchers and to consider how this may have an effect. Of course, this is not to say that single mothers do not face challenges and societal disadvantages – for as Hunter notes that among people who experience chronic stress, economic disadvantage, and discrimination, single mothers are overrepresented.

Yet as research findings have been lacking in showing the strengths and advantages of single mother families, an effort is needed “…to extend forms of fieldwork to include informal, narrative, and online sources as well as to commit to researcher reflexivity across all methodologies which acknowledge rather than ignore the embedded values of the researcher” (Hunter 236). As Bruno notes, many who now write about single motherhood object to framing single motherhood as an absence (386). Moving forward, researchers must acknowledge the effect that their work has on the lives and well-being of women and wider society: “[r]esearch that reinforces and reproduces a deficient evaluation of single-parent families requires re-examination” (Hunter 235). Hunter “...urges researchers to listen more carefully to the voices of women and respect their accounts of their own lives” (236).

“‘Single mother.’ Say it out loud in a grocery store, at school, in the park, on the news, or in a social service agency and all of the destructive and pathologizing images of a neglectful mother come to mind” (Ajandi 411). Structural and institutional disadvantage plays an important role in the creation of this, and more often than not does not reflect the reality of many mother-led households. While there are indeed single fathers who face their own challenges, "[t]he gendered reality of parenting alone [is] that it is still predominately women and mothers (‘women's work’) who are engaged in the bulk of the labour of childrearing" (Motapanyane 2).

At the most basic level, it is important to ask – who are single mothers? Bruno states that single mothers are “a group of women who are notoriously difficult to identify, let alone define” (385). The author understands single mothers as women who parent outside of the nuclear family structure, “but in no way assumes singleness indicates a lack of personal or parental companionship” (Bruno 385). In this way, it is noted that a single mother may or may not have other parental figures helping to raise their child. Single motherhood is also not always a static group - it is sometimes a temporary state, not a permanent one (Bruno 389). Bruno notes that “...single motherhood looks different for every woman…the diversity of terms for single motherhood (“single mother,” “lone mother,” “solo mother,” “female headed household,” etc.) reflects a ‘real diversity of meanings and experiences’”…[which also reflects] shifting ideologies over the last century” (388).

Families with single mothers at the head of the household are continuously seen as a second-hand, less-than-ideal option in Canadian society – and many others around the world. One reason for this is the perceived detriment it is seen to inflict: it is believed that single mother households are not good for children’s well being. This includes viewpoints that children raised by single moms are less likely to complete high school, and more likely to be neglected and/or raised in impoverished conditions. Hunter notes, “[h]ealth and social researchers overwhelmingly report poorer well-being for women and children in lone-mother or single-parent families, as compared with two-parent households…[r]esearch into life in mother-led or lone-mother households is dominated by negative accounts of deficit or survival” (222-228). Yet Hunter goes on to state,

research academies have been found to reflect a particular conservative, individualistic, and patriarchal valuing of well-being, women and children, as well as a preference for certain gender functions and the promotion of normative (nuclear) family forms…[s]ome researchers demonstrate a visible preference for the supposed benefits of living in two-parent families…beside such an agenda, lone-mother families continue to be viewed as deviant. (235)

In the face of such research, then, single mothers must overcome negative stereotypes and life narratives forced on them while simultaneously raising a child solo. Hunter asserts that it is important to assess the societal values of and around researchers and to consider how this may have an effect. Of course, this is not to say that single mothers do not face challenges and societal disadvantages – for as Hunter notes that among people who experience chronic stress, economic disadvantage, and discrimination, single mothers are overrepresented.

Yet as research findings have been lacking in showing the strengths and advantages of single mother families, an effort is needed “…to extend forms of fieldwork to include informal, narrative, and online sources as well as to commit to researcher reflexivity across all methodologies which acknowledge rather than ignore the embedded values of the researcher” (Hunter 236). As Bruno notes, many who now write about single motherhood object to framing single motherhood as an absence (386). Moving forward, researchers must acknowledge the effect that their work has on the lives and well-being of women and wider society: “[r]esearch that reinforces and reproduces a deficient evaluation of single-parent families requires re-examination” (Hunter 235). Hunter “...urges researchers to listen more carefully to the voices of women and respect their accounts of their own lives” (236).

At the most basic level, it is important to ask – who are single mothers? Bruno states that single mothers are “a group of women who are notoriously difficult to identify, let alone define” (385). The author understands single mothers as women who parent outside of the nuclear family structure, “but in no way assumes singleness indicates a lack of personal or parental companionship” (Bruno 385). In this way, it is noted that a single mother may or may not have other parental figures helping to raise their child. Single motherhood is also not always a static group - it is sometimes a temporary state, not a permanent one (Bruno 389). Bruno notes that “...single motherhood looks different for every woman…the diversity of terms for single motherhood (“single mother,” “lone mother,” “solo mother,” “female headed household,” etc.) reflects a ‘real diversity of meanings and experiences’”…[which also reflects] shifting ideologies over the last century” (388).

Families with single mothers at the head of the household are continuously seen as a second-hand, less-than-ideal option in Canadian society – and many others around the world. One reason for this is the perceived detriment it is seen to inflict: it is believed that single mother households are not good for children’s well being. This includes viewpoints that children raised by single moms are less likely to complete high school, and more likely to be neglected and/or raised in impoverished conditions. Hunter notes, “[h]ealth and social researchers overwhelmingly report poorer well-being for women and children in lone-mother or single-parent families, as compared with two-parent households…[r]esearch into life in mother-led or lone-mother households is dominated by negative accounts of deficit or survival” (222-228). Yet Hunter goes on to state,

research academies have been found to reflect a particular conservative, individualistic, and patriarchal valuing of well-being, women and children, as well as a preference for certain gender functions and the promotion of normative (nuclear) family forms…[s]ome researchers demonstrate a visible preference for the supposed benefits of living in two-parent families…beside such an agenda, lone-mother families continue to be viewed as deviant. (235)

In the face of such research, then, single mothers must overcome negative stereotypes and life narratives forced on them while simultaneously raising a child solo. Hunter asserts that it is important to assess the societal values of and around researchers and to consider how this may have an effect. Of course, this is not to say that single mothers do not face challenges and societal disadvantages – for as Hunter notes that among people who experience chronic stress, economic disadvantage, and discrimination, single mothers are overrepresented.

Yet as research findings have been lacking in showing the strengths and advantages of single mother families, an effort is needed “…to extend forms of fieldwork to include informal, narrative, and online sources as well as to commit to researcher reflexivity across all methodologies which acknowledge rather than ignore the embedded values of the researcher” (Hunter 236). As Bruno notes, many who now write about single motherhood object to framing single motherhood as an absence (386). Moving forward, researchers must acknowledge the effect that their work has on the lives and well-being of women and wider society: “[r]esearch that reinforces and reproduces a deficient evaluation of single-parent families requires re-examination” (Hunter 235). Hunter “...urges researchers to listen more carefully to the voices of women and respect their accounts of their own lives” (236).

Excerpt from Single-Lone Mothers: The Movement

This excerpt looks at advantages to female-led households.

This excerpt looks at advantages to female-led households.

So what, then, are the strengths and advantages to mother-led households? As Hunter notes, “[t]he qualities forged by women in lone-mother families, including safety or resilience, remain largely invisible or minimalized in public discourse” (229). One reward in a mother-led household includes a blurring of narrow, gendered identities. By taking over both parental roles, single mothers blur gender binary lines and create suspicion from those who see a clear need for both genders to be rearing children (assumedly, to ensure that children “correctly” adapt to the gender their society has prescribed for them, though it be merely a social construction). In one research article, “[m]any women reported that the men they had been partnered with insisted on restrictive binary codes of gender behaviour for their children and being single freed them from this limitation” (Ajandi 422).

In learning gender, children learn both a gender identity and to perform this identity in day-to-day life” (Berridge and Romich, 160). One example of how this translates day-to-day in mother-led households is through chores around the house. “In mother-only families, children spend nearly twice as much time on household chores as those in two-parent families…[t]his has been found to be true for both girls and boys” (Quoted in Berridge and Romich, 159). In Berridge and Romich, the authors “pay attention to both the instrumental role of work in helping run a household and the symbolic meaning of “women’s work” done by boys” (161).

The relationship between parent and child(ren) is also fundamentally altered in a single mother household. Zadeh and Foster notes, “[w]ith regard to single mothers by sperm donation, it is clear that media representations bear little relation to the psychological literature that has shown that this user group – and their children – are psychologically well adjusted, and their families are characterised by positive mother–child relationships” (561). Steer further notes:

Children in fatherless families experience…more interaction with their mother, and perceive her as more available and dependable…the children’s social and emotional development [is] not negatively influenced by the absence of a father, although boys in father-absent families showed more feminine but no less masculine characteristics of gender role behaviour (Quoted in Steer, 175).

As feminine characteristics are often associated with traits such as kindness, sensitivity, and empathy, such a balance can be seen as a positive step towards reducing hegemonic masculinity.

Another advantage to single motherhood is more decision making power regarding raising children. Ajandi notes,

Many women felt privileged to be single mothers because it gave them the freedom to be the sole decision-maker for the family. They were able to raise their children with their own values and did not need to negotiate these decisions with a partner… [s]ome women felt that even though they experienced barriers and being a single mother student was a 24-hour job, not having the other partner to take care of reduced their burden significantly (Ajandi 418).

In connection to this, Ajandi notes that feelings of independence contributed to elevating single mothers’ perceptions of self-esteem and self-worth. “The obstacles they overcame daily gave them the strength and resiliency to believe in themselves in ways that they often did not when they were in relationships” (Ajandi 419). As Ajandi says, there are “many rewards and possibilities that make this [single mother] family status desirable and rich with possibilities” (410).

In learning gender, children learn both a gender identity and to perform this identity in day-to-day life” (Berridge and Romich, 160). One example of how this translates day-to-day in mother-led households is through chores around the house. “In mother-only families, children spend nearly twice as much time on household chores as those in two-parent families…[t]his has been found to be true for both girls and boys” (Quoted in Berridge and Romich, 159). In Berridge and Romich, the authors “pay attention to both the instrumental role of work in helping run a household and the symbolic meaning of “women’s work” done by boys” (161).

The relationship between parent and child(ren) is also fundamentally altered in a single mother household. Zadeh and Foster notes, “[w]ith regard to single mothers by sperm donation, it is clear that media representations bear little relation to the psychological literature that has shown that this user group – and their children – are psychologically well adjusted, and their families are characterised by positive mother–child relationships” (561). Steer further notes:

Children in fatherless families experience…more interaction with their mother, and perceive her as more available and dependable…the children’s social and emotional development [is] not negatively influenced by the absence of a father, although boys in father-absent families showed more feminine but no less masculine characteristics of gender role behaviour (Quoted in Steer, 175).

As feminine characteristics are often associated with traits such as kindness, sensitivity, and empathy, such a balance can be seen as a positive step towards reducing hegemonic masculinity.

Another advantage to single motherhood is more decision making power regarding raising children. Ajandi notes,

Many women felt privileged to be single mothers because it gave them the freedom to be the sole decision-maker for the family. They were able to raise their children with their own values and did not need to negotiate these decisions with a partner… [s]ome women felt that even though they experienced barriers and being a single mother student was a 24-hour job, not having the other partner to take care of reduced their burden significantly (Ajandi 418).

In connection to this, Ajandi notes that feelings of independence contributed to elevating single mothers’ perceptions of self-esteem and self-worth. “The obstacles they overcame daily gave them the strength and resiliency to believe in themselves in ways that they often did not when they were in relationships” (Ajandi 419). As Ajandi says, there are “many rewards and possibilities that make this [single mother] family status desirable and rich with possibilities” (410).

Excerpt from Single Mothers as Leaders

This excerpt looks at some of the ways in which single-lone mothers lead

This excerpt looks at some of the ways in which single-lone mothers lead

In Ajandi’s research of single mothers attending university, she found “[m]any single mother students became activists and advocates against oppression and structured their families to be active in social justice issues” (421). While there were instances of single mothers helping other single mothers, this was typically not the case. Rather than focusing on themselves as a group, single mothers were found to be involved in fighting against many different types of oppression. “As Karina [a participant in the study] noted, ‘Social justice isn’t just about fighting for equity and inclusion in one community, but seeing how all communities are linked and learning how to become an ally – all injustices are interconnected’” (Ajandi, 421). As Ajandi notes,

Many of the co-participants in the study were already studying in critical fields such as Social Work, Women and Gender Studies, Aboriginal Studies, Diaspora Studies, and Sociology, or wanted to move into “helping professions”. As they put it, having these difficult and rewarding experiences in their lives made them aware of how marginalized people are denied access to resources and are stigmatized in society. Their own struggles gave them a unique perspective with respect to understanding of, identification with, and empathy toward those experiencing barriers. (423)

Many women were also involved in on-campus initiatives, programs, and activist groups that “sought to challenge oppressive systems in society, such as anti-ableism, anti-racist, antiheterosexist, and union groups” (Ajandi, 422).

Many of the co-participants in the study were already studying in critical fields such as Social Work, Women and Gender Studies, Aboriginal Studies, Diaspora Studies, and Sociology, or wanted to move into “helping professions”. As they put it, having these difficult and rewarding experiences in their lives made them aware of how marginalized people are denied access to resources and are stigmatized in society. Their own struggles gave them a unique perspective with respect to understanding of, identification with, and empathy toward those experiencing barriers. (423)

Many women were also involved in on-campus initiatives, programs, and activist groups that “sought to challenge oppressive systems in society, such as anti-ableism, anti-racist, antiheterosexist, and union groups” (Ajandi, 422).

Excerpt from Great Lakes to Great Walls

This excerpt looks at my own personal experience of single-lone motherhood

This excerpt looks at my own personal experience of single-lone motherhood

"I can say with complete certainty that my life, and my son’s, could not have been as wonderful as it is now had I not raised Zac as a single parent given my choices at the time. Perhaps this sounds like a bold claim, but as MacCollum and Golumbok point out, “children in fatherless families experience…more interaction with their mother, and perceive her as more available and dependable…the children’s social and emotional development [is] not negatively affected by the absence of a father, although boys in father-absent families showed more feminine but no less masculine characteristics of gender role behaviour” (x). When feminine characteristics are socially constructed and encompass traits like kindness, sensitivity, and empathy, I can only agree with Ajandi that there are “many rewards and possibilities that make this [single mother] family status desirable and rich with possibilities” (410)" (Steer).